By: Gerelyn Terzo of Sharemoney

Brazil’s economy was already in trouble before the pandemic hit. By the time that COVID-19 arrived, however, things went from bad to worse in a hurry. Brazil suffered a 4.1% decline in GDP last year, which was less bad than feared, but which reflects the most severe annual recession since this wave of economic contraction began in the mid-nineties. While many countries are setting out on the path to recovery after the coronavirus year, Brazil is going to have to take some positive steps to dig itself out of the economic hole it has dug.

With unemployment hovering at an all-time high of 14%, the number of Brazilians living in poverty has skyrocketed in the past year, according to The Economist. The percentage of poverty-stricken Brazilians has more than doubled from 4.2% before COVID hit to 11.4% prior to the distribution of government aid. With government support that percentage eased to 3.7%.

Not only has poverty gripped the Latin American nation but Brazil has the dubious distinction of being among the countries with the highest number of COVID-related deaths in the world, second only to the United States. This has been blamed on a one-two punch of government officials mired in denial about the severity of the health crisis in an attempt to keep the economy open, which ultimately backfired, and a new variant that is spreading across the nation, all of which has thrown a wrench into economic recovery.

Food Inflation

Adding insult to injury is the fact that food inflation is on the rise in Brazil, which given its status as the largest economy in the Latin American region could cause ripple effects. Here again, Brazil takes the title for seeing food prices skyrocket the fastest in comparison with broader inflation amid the falling value in the currency, the real, outpacing the government’s ability to foster aid.

Higher food prices have fueled an increase in overall inflation in the country to levels not seen in nearly two decades. In October 2020, Brazilians saw the price tag on staple items soar by double-digit percentages, including the cost of rice, whose price rose more than 75% last year, as well as whole milk and beef, which saw prices rise more than 20%.

Incidentally, the government appears to have shot itself in the foot on this one, as the stimulus funds distributed to the Brazilian population went largely toward food. That’s because the segment of the population that received relief funds counts food as their highest expense, which triggered a spike in demand and resulted in higher food prices.

Green Shoots

Despite the dire outlook, there are some green shoots of recovery taking place in Brazil’s economy. For example, Mottu, a Sao Paulo-based motorcycle-as-a-service startup, recently secured the backing of global institutional investors in a Series A fundraising round. Participants included the likes of Tiger Global Management and venture capitalists such as Nubank founder David Velez, who has been dubbed the “face of Latin American fintech.”

The company plans to direct the proceeds toward delivering solutions for gig-economy workers, such as couriers, who can’t otherwise afford the necessary tools to participate in the burgeoning e-commerce market. Mottu rents motorcycles for an average of USD 4.40 per day to Brazilians who are unbanked, also serving as a marketplace to match couriers and retailers who can help each other out.

Elsewhere, the FGV Office of Research and Innovation recently hosted the “First EU-Brazil conference on digital economy and innovation.” The goal of the webinar was to find areas where the EU and Brazil could partner on digital trade and emerging technologies, with a focus on priorities such as the blockchain, supercomputing use cases in healthcare, 5G, artificial intelligence, IoT and data protection, for instance.

Participants ranged from the world of academia, government officials, and companies including the aforementioned Nubank, which created a dialog on how to nurture cooperation in technology innovation between EU institutions and Brazil. One example of this is FUTEBOL, which stands for the Federated Union of Telecommunications Research Facilities for an EU-Brazil Open Laboratory. The mission of this project is to “allow access to advanced experimental facilities in Europe and Brazil for research and education across the wireless and optical domain.”

The Path Forward for Brazil’s Economy

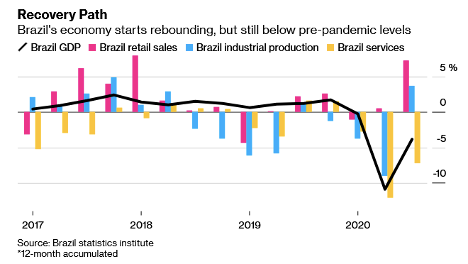

Identifying the path forward for Brazil’s economy requires taking a step back. After suffering from its most severe economic slowdown in history in Q2 2020, Brazil experienced a 7.7% jump in economic growth in Q3. The increase was a reflection of a flood of government stimulus that was issued in an attempt to stem the tide of the economic slowdown. Now that the virus has reared its ugly head once again, the Brazilian government is grappling with how to pay for the hundreds of billions of dollars in total relief funds. In Q4, GDP expanded 3.2%.

Most recently, Brazil has approved an USD 8 billion emergency stimulus deal, which pales in comparison to the size of its previous relief packages. While the plan is being cheered for “[supporting] consumption while limiting the effects on fiscal accounts,” not everyone is celebrating.

A bedrock of the stimulus package was a stipend that was distributed to Brazilian citizens that actually helped to relieve some of the poverty in the nation. Policymakers have trimmed the amount of the cash transfers in the latest stimulus round after the country’s debt ballooned to 90% of its GDP. The new stipend is for USD 45 per month for four months.

Meanwhile, Brazilians like construction worker Rubinarht Almeida, who was featured by Bloomberg, are stuck between a rock and a hard place. Almeida depended on the stipend payments to keep him afloat after finding himself on the unemployment line as a result of COVID. Now he is looking to switch industries to work as a doorman, which also makes him vulnerable to the virus.

Where Brazil’s economy goes from here depends largely on how the pandemic plays out. Current estimates are for the economy to grow at a rate of 3-3.5% this year. At the same time, however, the country is facing pressure to issue a complete lockdown to control the latest wave of the virus. And in order for any economic recovery to be sustainable, Brazil is going to have to attract foreign investment back to the country so the debt-to-GDP ratio can recover, Brookings Institute pointed out. Any way you slice it, however, it appears that economic growth over the coming decade will be slower than predictions from the pre-pandemic days.

Entrepreneur Resources Your source for small business information

Entrepreneur Resources Your source for small business information